Joe Dodge - AMC Shelter Manager - Pinkham Notch

Except for an occasional road crossing and shelter, Lonesome Lake Hut is the first sign of civilization on the Appalachian Trail in New Hampshire since Hanover, 67 miles to the south. The hut — more like a hiker hotel — sits at the south end of eight high-country huts in the White Mountains. For the next 62 miles along the roughest and prettiest section of the Whites, hikers can sleep and eat in relative luxury, carrying just water and a raincoat. And that is due to one tough son-of-a-bitch named Joe Dodge.

The hut marks the edge of the empire mountain legend Dodge built out of sheer muscle and brains during his 51 years in the Whites. In 1922, he left Manchester-by-the-Sea, Mass., and his family’s lucrative furniture business. A decade later he had rebuilt all five huts in the Appalachian Mountain Club System, then built three new ones in some of the most inaccessible plots of land in the Northeast. Between 1927 and 1931, Dodge’s crews of men, burros and in one case a tractor hauled a combined 210 tons of material up the mountains to complete the projects. If the story ended there, it would be enough for a life work. But it doesn’t. William Lowell Putnam closed the introduction to his 1985 biography, “Joe Dodge: One New Hampshire Institution,” with this challenge: “If you didn’t know Joe Dodge, you damn well should have.”

From a young age, Dodge began a lifelong habit of uniting people with their love. Dodge’s son, Joseph Brooks Dodge Jr., said, “The old man ran one of the first private radio stations in the country, call sign W1UN.” When ships were approaching Boston or New York City, they would call the elder Dodge in Manchester, Mass., and ask him to call or telegraph their wives or girlfriends to say they’d be docking soon. “There was always an understanding that they’d reimburse him for every call or telegraph,” said Dodge’s son. And with one exception, everyone did.

To his parents’ dismay, Dodge left high school at 17 to join the U.S. Naval Submarine Service as a radio operator. When he returned, Dodge’s parents wanted him to attend the prestigious Phillips Andover Academy, but “he didn’t want any part of that,” recalled his daughter, Anne Dodge Middleton. “He’d been with a bunch of men during the war, and he didn’t want to go back to kids.” So in 1922, after an argument with his older brother, 23-year-old Joseph Brooks Dodge left Manchester, Mass., climbed into a Model-T truck with three friends and rode north. He became the hutmaster at the AMC lodge in Pinkham Notch — nicknamed “Porky Gulch” for the number of porcupines. He soon became “The Mayor of Porky Gulch.” In 1925, Dodge had just three mountain huts to check on.

Since Pinkham Notch closed in late fall, Dodge spent the first four winters “timber cruising” for a Maine lumber company — walking back and forth along a section of woods to estimate the usable lumber. Then on October 16, 1926, he was summoned to Boston to meet with the AMC Hut Committee. Thinking they might question him about finances, he brought stacks of balance sheets. But they surprised him by asking if he’d like to keep the lodge at Pinkham Notch open year-round and check for winter vandalism at the other huts. Dodge agreed on the spot. He drove his old Ford, nicknamed “Azma,” back to the Notch, and Pinkham Notch Lodge — now Joe Dodge Lodge — never closed again.

His pay in those early days was $20 a week. If he wanted supplies, he strapped on skis and traveled the 22-mile roundtrip to Gorham, loaded on the return with 80-100 pounds in his rucksack. And often his preferred bathing method was to roll naked in the snow or take a dip in the icy waters of the Cutler River. Not ideal conditions to start a family, but that didn’t stop Dodge. Snowbound in February 1927, he told a fellow ham radio operator to relay his marriage proposal. “I’m lonesome as hell up here,” Dodge bellowed into his mic. “Call up Cherstine Peterson over in Cambridge. See if she’d like to come up and join me.” When she accepted, Dodge sent back an order for her to pick up an engagement ring.

After a wedding in Boston on October 26, 1927, Dodge and his new bride were trying to return from their honeymoon to Pinkham Notch. The highway at Bethel, Maine, was washed out from the destructive flood of November 3, 1927. So Dodge drove his car across a Grand Trunk Railroad trestle, managing his marriage as he would manage the huts — rigging up whatever was handy to get the job done.

Surviving the 1927 flood, Dodge became interested in weather observing. He told the Lisbon Courier in 1966, “The heavy rains ran off the hillsides like falling from a tin roof and caused a great amount of highway and culvert damage.” A Dartmouth professor organized a network to gather precipitation data, and naturally, Dodge took charge of the effort in the North Country. He became the Weather Bureau’s official observer at Pinkham Notch, and from then to his death Dodge or his assistants provided data.

Surviving the 1927 flood, Dodge became interested in weather observing. He told the Lisbon Courier in 1966, “The heavy rains ran off the hillsides like falling from a tin roof and caused a great amount of highway and culvert damage.” A Dartmouth professor organized a network to gather precipitation data, and naturally, Dodge took charge of the effort in the North Country. He became the Weather Bureau’s official observer at Pinkham Notch, and from then to his death Dodge or his assistants provided data.

On New Year’s Day, 1928, he became AMC Huts Manager, inheriting the main building at Pinkham and four remote huts. He held that job for 31 years to the day. In 1929-1930, Dodge hauled, hammered, cussed and inspired his crew to build Greenleaf Hut, on the side of Mt. Lafayette. Over the next year, he built Galehead Hut, the most remote hut in the White Mountains, by cutting trees on Garfield Ridge. And that summer, Dodge and crew also hauled 40 tons of material up an old logging railroad bed during one of the wettest Junes in history to build Zealand Falls Hut, completing the links of eight huts in the White Mountains. Through good business sense and a paradox of hard-cussing diplomacy, Dodge finished building the huts nearly 40 percent under budget.

“Little does the casual tramper realize the days of heartbreaking labor that go into the construction of a hut above tree line,” wrote Dodge in Appalachia in 1932. Dealing with bad weather, “labor turnover” and the backbreaking effort of transporting construction materials over rocky, steep mountain trails kept him awake many nights “figuring out the morrow.”

The three new huts built between 1929 and 1931 — Greenleaf, Galehead and Zealand Falls — represented an innovation in both style and substance. Dodge was the AMC’s first in-house construction boss for such a large project, and the huts — with both kitchens and bunkrooms — were a giant leap in creature comforts from the shelters of the past. The increased luxury would prove to be a worthwhile gamble. In the process, he increased revenues from $13,000 a year when he took over to more than $100,000 a year by 1949.

More than a tough taskmaster, Joe Dodge became the prime diplomat of the White Mountains. One writer estimated that Dodge knew 2,000 people by name and had met another 250,000. The White Mountains were his love, and he wanted to introduce them to the world. He was handsome, with piercing blue eyes. Barrel-chested, Dodge had a voice that could shake snow off trees. He could entrance visitors — goofers — with fictitious stories of the spike-tailed dingmaul and the green-whiskered cumatabody. Dodge enjoyed life, and he was happy telling stories in his uniquely profane way. “His language was pretty raw,” agreed his son. “People were shocked the first time, but after that they loved it.” Beyond the standard cussing, he’d say crappertories for lavatories, Hangover for Hanover; and for a newspaper? “By gees,” Joe would say, “hand me that fishwrapper there.” Manchester-by-the-Sea, he once said on live radio, was near “Gloucester-by-the-smell.”

A scientist as well as an outdoorsman, in September 1932, Dodge and three others started the Mt. Washington Observatory, which gathered key data on extreme weather conditions, with a $400 grant from the N.H. Academy of Science. The timing was perfect. Eighteen months later, on April 12, 1934, the strongest wind in the world, 231 mph, was recorded at Mt. Washington, atop the sturdy summit weather station. In his biography Dodge said of the grant, “That was one helluva lot of money in those depression days, and it was the greatest morale boost I’ve ever had … People think of me as the AMC’s man in these parts; but, I’ll tell you that in my heart I think of myself as the Observatory’s man. I think I’ve done a damn sight more for the long-range good of humanity with the Observatory than with the Hut System.” The Observatory began 24-7 operation that year; added government grants to study jet-engine technology; and grew to 20 employees with a $1.5 million annual budget by 2005. Dodge remained managing director throughout its growth and treasurer until his death in 1973.

Between building huts and starting the observatory, Dodge also rescued countless hikers. Estimates of rescues he led or directed run to over 100. In 1949, the year Dodge turned 50, The Saturday Evening Post ran a seven-page feature, in which Dodge related his rescue technique: “My theory… is that if some damn goofer is lost, you should figure what any sensible person would do, and then look in the opposite direction.” His theory worked. Dodge had a spooky knack for rescuing hopelessly lost hikers. In one of his most famous rescues, Dodge saved the life of Harvard Egyptologist and experienced climber Jessie Whitehead. Whitehead had broken her neck and shoulder, suffered five fractures in her jaw and severe wounds on her head and neck when she and a companion fell 800 feet down Odell Gully on the side of Mount Washington. During the necessarily rough stretcher ride down the mountain, a deep cut on Whitehead’s neck hemorrhaged, so Dodge stuffed snow in the gaping hole. “It was rough,” he told the Boston Herald, “but it worked, blast it.” Which was true for many of his accomplishments.

Dodge left a legacy in skiing. The Saturday Evening Post called Dodge “the best-known winter sportsman” in 1949 and estimated that 150,000 people had made their way to Dodge’s backyard to ski Tuckerman’s Ravine. Dodge’s son Brooks went on to compete in the 1952 Olympics in Oslo, Norway.

Dodge also left a legacy with the hundreds of men and women he hired as part of the hut crew. Brooks said his dad gave “absolutely great advice.” In 1945, Dodge told his son he was going to be the hutmaster at Madison.

“But all these older guys are coming back from the service,” the 15-year-old told his dad. Six decades later, Brooks still remembers “the old man’s advice.” “Lead with your actions, and keep your damn mouth closed. You don’t lead men with your mouth. You lead them by showing them you can do a better job at anything there is.”

Dodge’s legacy continues to grow. In 2005, more than 37,000 people spent a night in one of the AMC huts. In a time when the word “legend” gets cheapened to include someone who can run with a football in the afternoon and broker a drug deal in the evening, Joe Dodge remains the quintessential Real Thing.

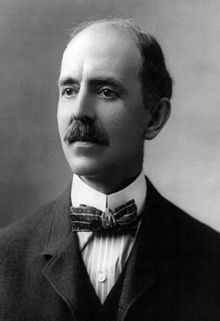

Daniel Chester French - Sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial

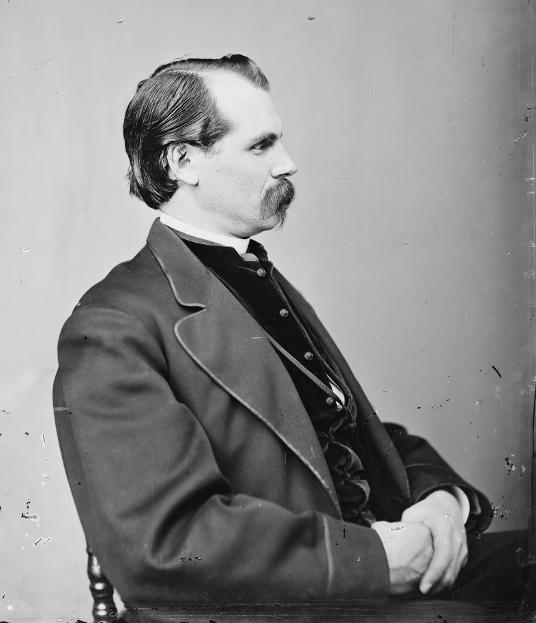

Sarah Josepha Hale - Mother of Thanksgiving Day

On October 3, 1863, with the nation embroiled in a bloody Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation setting aside the last Thursday in November as a national day of thanks, setting the precedent for the modern holiday we celebrate today.

Secretary of State William Seward wrote it and Abraham Lincoln issued it, but much of the credit for the proclamation should probably go to a woman named Sarah Josepha Hale. A prominent writer and editor, Hale had written the children’s poem “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” originally known as “Mary’s Lamb,” in 1830 and helped found the American Ladies Magazine, which she used a platform to promote women’s issues. In 1837, she was offered the editorship of “Godey’s Lady Book,” where she would remain for more than 40 years, shepherding the magazine to a circulation of more than 150,000 by the eve of the Civil War and turning it into one of the most influential periodicals in the country. In addition to her publishing work, Hale was a committed advocate for women’s education (including the creation of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York), and raised funds to construct Massachusetts’s Bunker Hill Monument and save George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate.

The New Hampshire-born Hale had grown up regularly celebrating an annual Thanksgiving holiday, and in 1827 published a novel, “Northwood: A Tale of New England,” that included an entire chapter about the fall tradition, already popular in parts of the nation. While at “Godey’s,” Hale often wrote editorials and articles about the holiday and she lobbied state and federal officials to pass legislation creating a fixed, national day of thanks on the last Thursday of November—a unifying measure, she believed that could help ease growing tensions and divisions between the northern and southern parts of the country. Her efforts paid off: By 1854, more than 30 states and U.S. territories had a Thanksgiving celebration on the books, but Hale’s vision of a national holiday remained unfulfilled.

The concept of a national Thanksgiving did not originate with Hale, and in fact the idea had been around since the earliest days of the republic. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress issued proclamations declaring several days of thanks, in honor of military victories. In 1789, a newly inaugurated George Washington called for a national day of thanks to celebrate both the end of the war and the recent ratification of the U.S. Constitution—one of the original copies of Washington’s proclamation is set to be auctioned this November, with an estimated sale price of $8-12 million. Both John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations of their own, though fellow Founding Father Thomas Jefferson felt the religious connotations surrounding the event were out of place in a nation founded on the separation of church and state, and no formal declarations were issued after 1815.

The outbreak of war in April 1861 did little to stop Sarah Josepha Hale’s efforts to create such a holiday, however. She continued to write editorials on the subject, urging Americans to “put aside sectional feelings and local incidents” and rally around the unifying cause of Thanksgiving. And the holiday had continued, despite hostilities, in both the Union and the Confederacy. In 1861 and 1862, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had issued Thanksgiving Day proclamations following Southern victories. Abraham Lincoln himself called for a day of thanks in April 1862, following Union victories at Fort Donelson, Fort Henry and at Shiloh, and again in the summer of 1863 after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Shortly after Lincoln’s summer proclamation, Hale wrote to both the president and Secretary of State William Seward, once again urging them to declare a national Thanksgiving, stating that only the chief executive had the power to make the holiday, “permanently, an American custom and institution.” Whether Lincoln was already predisposed to issue such a proclamation before receiving Hale’s letter of September 28 remains unclear. What is certain is that within a week, Seward had drafted Lincoln’s official proclamation fixing the national observation of Thanksgiving on the final Thursday in November, a move the two men hoped would help “heal the wounds of the nation.”

After more than three decades of lobbying, Sarah Josepha Hale (and the United States) had a national holiday, though some changes remained in store. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt briefly moved Thanksgiving up a week, in an effort to extend the already important shopping period before Christmas and spur economic activity during the Great Depression. While several states followed FDR’s lead, others balked, with 16 states refusing to honor the calendar shift, leaving the country with dueling Thanksgivings. Faced with increasing opposition, Roosevelt reversed course just two years later, and in the fall of 1941, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution returning the holiday to the fourth Thursday of November.

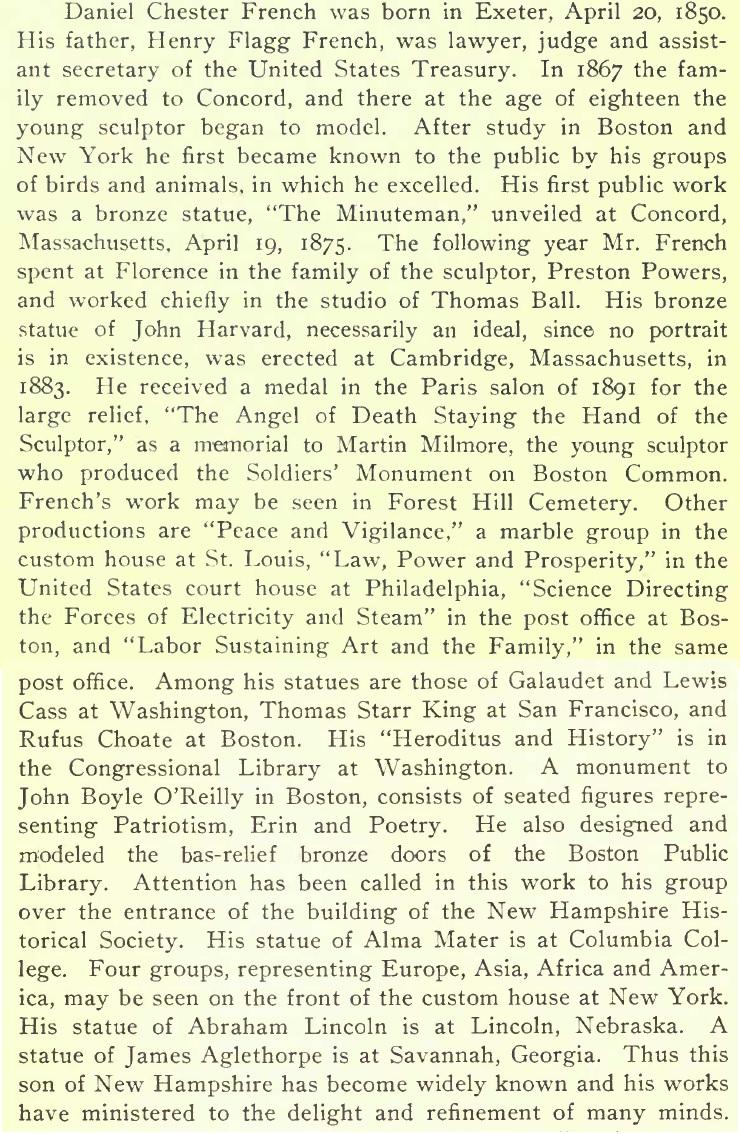

Thaddeus S.C.Lowe - US Army's First Aeronaut

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe was born August 20, 1832 in Jefferson Mills, New Hampshire. Intellectually curious and driven from a young age, Lowe had almost no formal education but demonstrated an appetite for learning which hinted at his future career as an inventor. At the age of 18 he attended a lecture on the subject of lighter-than-air gases and so impressed the professor, Reginald Dinkelhoff, with his enthusiasm that Dinkelhoff offered to take the young Lowe on the lecture circuit with him as an assistant. Over the course of the next decade, Lowe devoted himself to balloon aviation, and became a prominent builder of balloons and showman. In 1855, at one of his demonstrations, he met the Parisian actress Leontine Augustine Gaschon, and they were wed just one week later. The couple eventually had ten children. In the latter part of the decade he set about building bigger balloons, with an eye towards a transatlantic crossing, and began to garner a prominent scientific reputation. In April, 1861, Lowe intended to make a test run from Cincinnati, Ohio to Washington, D.C. He took off on April 19, just a week after the fall of Fort Sumter, but instead of heading due east towards Washington Lowe’s balloon was blown way off course, eventually landing in Unionville, South Carolina. There, he was arrested on suspicion of being a Northern spy. When he finally convinced the Confederate authorities of his innocence he returned to Cincinnati, only to be immediately summoned to Washington. The government was in fact interested in his experimental balloons as a means of gathering intelligence.

In June of 1861, Lowe demonstrated for President Lincoln how useful his balloons could be when combined with new electric telegraph technology. On the 11th of that month, from a height of 500 feet above the National Mall in Washington D.C., Lowe transmitted to the President: “This point of observation commands an extent of country nearly 50 miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments, presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station, and in acknowledging indebtedness for your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of the country.” Little more than a month later, Lowe and his balloon were in action during the First Battle of Bull Run, after which Lincoln approved the formation of the Union Army Balloon Corps, with Lowe as Chief Aeronaut (at a colonel’s salary). Lowe’s principal contribution to the militarization of balloon technology, and its use in the field, was the portable hydrogen gas generator, which allowed the balloons to accompany the army wherever they were needed. Made of a rugged material that could withstand the wear and tear of active campaigning, Lowe’s balloons could also be inflated in a very short amount of time. They were a sensation in Washington, and many prominent military and political figures accompanied him on his ascensions. He eventually built a total of seven balloons and twelve generators for the war effort.

In the spring of 1862, Lowe and his balloons played a significant role in the Peninsula Campaign, observing the enemy’s defensive dispositions and helping relay information during the slow but steady advance on Richmond. At the Battle of Seven Pines, Lowe’s aerial reconnaissance helped identify the buildup of Confederate forces near the Fair Oaks train station prior to the start of the battle. In addition to providing valuable aerial reconnaissance information, Lowe, when supported with direct telegraphic links to commanders, was able to provide near real-time artillery spotting to Army of the Potomac artillery units. While operating from Dr. Gaines’ farm on the future Gaines’ Mill battlefield, Lowe was positioned close enough to Richmond that he could clearly see the movements of soldiers and individuals within the city. The sight of Lowe’s balloons, ominously hanging over the Virginia landscape, certainly must have unsettled the Confederates, who knew their movements were being observed by the enemy. While several attempts were made to destroy the Union balloons via long range artillery fire, none of Lowe’s balloons were ever damaged or destroyed in combat. Though Lowe and his balloons were able to avoid damaging enemy fire, Lowe himself contracted a serious bout of malaria from the mosquito infested waters near the Chickahominy River.

After the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign, Lowe’s Balloon Corps was utilized during the 1862 Fredericksburg and 1863 Chancellorsville campaigns. During this period, some Union commanders and leaders began to question Lowe’s heavy expenditures and poor administrative skills. Placed under a more controlling military command structure, the frustrated and sick Lowe resigned from his balloon corps and the use of balloons within the Union armies ended shortly afterwards.

Lowe returned to the private sector following the war, and made a fortune developing ice-making machines before moving to Los Angeles, California in 1887. He died at his daughter’s home in Pasadena in 1913, aged 80

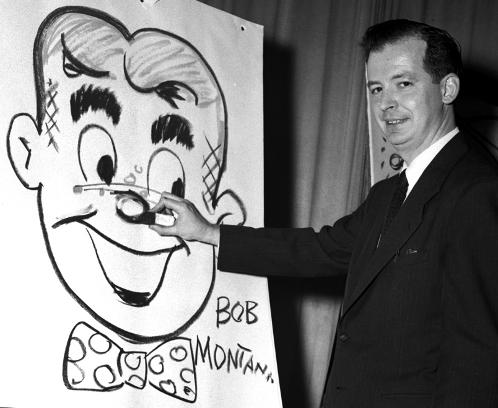

Bob Montana - Creator of the Archie Comic Series -

Resident of Meredith

Bob Montana was born in Stockton, California, but traveled extensively as a child due to his parents' occupations. He spent his school summers in Meredith, New Hampshire, where his father raised vegetables and operated a restaurant and it was there that Bob practiced his cartooning by drawing caricatures of the restaurant's customers. When Bob was 13, his father died of a heart attack, and his mother remarried.

In his senior year of high school, Bob moved with his parents to Manchester, New Hampshire and graduated from Manchester High School Central in 1940.

Following graduation, Bob moved to New York and attended the Art Students League and the Phoenix Art Institute. He soon began freelancing and created an adventure strip about four teenage boys which he tried to sell without success. Bob started working for MLJ Comics and was eventually asked to work up a high school style comic strip story. At age 21, he created Archie. The success of the character in MLJ's Pep Comics December, 1941 led MLJ to assign Bob to draw the first issue of Archie In November, 1942.

Bob spent four years in the Army Signal Corps during World War II, drawing coded maps, and working on training films. In 1944, while stationed at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, he met 19-year-old Army secretary, Helen (Peggy) Wherett, a native of Asbury Park, New Jersey. In 1946, the couple married and moved to Manhattan for a short while before returning to Meredith in 1948, where they bought an old New England-style farmhouse. In New Hampshire, they raised four children along with organic vegetables, assorted chickens, horses and sheep.

Bob continued to draw Archie for the rest of his life. After hours at his drawing table, it was his custom to relax by sailing his sloop, the White Eagle, on Lake Winnipesaukee, or skiing cross country near his home. He died of a heart attack on January 4, 1975, while cross-country skiing in Meredith. He was 55 years old

.